Introduction

In using dental microwear analysis, researchers attempt to reconstruct the diet and ecology of extant animal species, as well as attempt to provide quantitative explanations as to why certain behaviours in nature are expressed in one group and not in another, despite occupying the same ecological niche. The transition from two-dimensional dental tools to three-dimensional, was important to understanding teeth as having multiple facets with varying functions that interact with each other to produce unique patterns on dental enamel surfaces. The eventual discovery of varying degrees of hardness of the food an animal consumes, and grit that often encompasses it, as well as the effects of seasonality, illustrate the complexity of dental microwear patterns – its interpretation is dependent on the species studied and the question asked. Though dental microwear patterns can provide insight into the individual’s last few moments of life, and often optimistically assumed to also indicate the climate and surrounding environment, this report highlights the complexity of microwear analysis, its limitations and potential improvements.

Clues to dietary reconstruction and dental adaptations can be found from comparing wear behaviour patterns in different animal species (Constantino et al. 2015). The functionality of the teeth and thus the lifespan of primates and mammals are limited to enamel wear patterns (Spradley et al. 2015). This is due to having two sets of teeth that do not repair themselves, limiting their feeding ecology to their ability to gain sufficient energy, to produce and raise offspring (Spradley et al. 2015). All wild animals show some degree of dental wear (Constantino et al. 2015) and are commonly recognized as dietary signals (Spradley et al. 2015). Microwear, even at low forces – such as from soft foods that produce enamel scratches from hard particulates, can be read in microwear data analyses (Constantino et al. 2015). Clues to dietary reconstruction and dental adaptations can also be inferred from comparing wear behaviour patterns in different animal species (Constantino et al. 2015). Dental microwear is a result of the interaction between dental tissue and the external environment, and is also important when considering the seasonal changes in environment; which can then be used to study the effects of long-term climate change (Pineda-Munoz et al. 2017).

Why study teeth?

The morphology and developmental trajectory of an animal is influenced by its biotic and abiotic interactions, in relation to their individual life history traits (Percher et al. 2017). Diet, food processing techniques and exogenous abrasives, are all factors that can contribute to the progression of dental wear (Fiorenza et al. 2018). Dental remains are the best elements to track functional morphology variability within a population, because their structurally and chemically good preservation enables the specimens to be commonly readily identifiable in the paleontological record (Belmaker 2018).

Difference between Macrowear and Microwear

Dental microwear records the ante-mortem micro-features on tooth enamel caused by abrasion by food and exogenous particles, and its frequency depends on the rate at which the food is ingested (Belmaker 2018), reflecting the individual’s diet over its last few weeks to months alive (Percher et al. 2017). In contrast, macrowear is the cumulative process that occurs throughout the individual’s lifetime (Fiorenza et al. 2018) and is observed on wear facets, where wear exposes the underlying dentin (Constantino et al. 2015). Microscopic wear is typically informative of immediate effects of commonly ingested food items, whereas macrowear is the result of the totality of wear produced from long term wear use from the foods’ physical properties and short term ingestion of exogenous grit, which further weakens the developing tooth enamel (Spradley et al. 2015).

History of Microwear

Many of the early 19th century studies on tooth wear focused on occlusion, wear patterns and facet development, in the 1930s studies moved to focus on the the mechanical properties of food, and in recent decades saw the development of studies on the relationship between macro-level wear, jaw movements and diet (Belmaker 2018). The hardness of enamel functions to protect from abrasion; its damage-tolerant features is owed to its constitutive crystallites that can accomodate an indentation without fracturing (Lucas et al. 2013). There have been experiments that support the view that anatomical adaptations, such as hypsodonty, had evolved to combat quartz abrasion by prolonging dental function (Lucas et al. 2013). Enamel has been related to resembling ‘tough’ ceramic materials that allow for micro-cracking in a confined region while inhibiting any possibility of catastrophic fractures (Lucas et al. 2013). The act of rubbing on the enamel surface over time will eventually lead to wear, and only through more frequent contacts will cracks incur detaching the tissue (Lucas et al. 2013).

Causes and Indirect Measures of Microwear

Microwear is described as the removal of dental enamel or dentin caused by dental attrition or abrasion from ingested particles that had contact with tooth surfaces under chewing forces (Percher et al. 2017). Microwear is observed initially through the estimation of the mechanical properties of the food items consumed, as well as the observed features of the manipulation of such items (Percher et al. 2017). “Hard” foods are seeds or fruits with hard exocarps (Percher et al. 2017). In contrast, “tough” items refer to leaves, stems and roots, while “soft” foods are classified as flowers, mushrooms and soft fruits (Percher et al. 2017). Monocotyledonous plants also need to be distinguished from dicotyledonous plants because the Monocotyledonous plants generally show higher phytolith contents than the latter (Percher et al. 2017); distinguishing between these plants are important because those that consume plants with high proportions of phytoliths or those that incorporate dirt and grit while they eat, is indicative an animal that feed on graze or other low vegetations, thus display characteristically low and blunt cusps (Belmaker 2018). Even for arboreal species, dust accumulated in the trees and from the surrounding environment still suggests grit as a potential source of wear (Spradley et al. 2015).

Methods in Measuring Microwear

The three primary methods for measuring microwear are: surface imaging through SEM; imaging the surface using low magnification stereomicroscopy; and 3D microscopy using white-light or laser-scanning confocal microscopy, focus variation microscopy and profilometry, to analyze the surface texture variables – known as DMTA, or dental microwear texture analysis (Belmaker 2018). SEM was the standard for studying microwear and the relationship between enamel wear and diet since the late 1970s due to its higher resolution and increased field of depth in comparison to stereomicroscopes (Belmaker 2018). This feature allowed researchers to observe and analyze the sub-micro wear patterns that are not generally observed using stereomicroscopy (Belmaker 2018). The main problems with using 2D approaches such as SEM, optical photomicrographs and optical microscopy, is that these techniques require human operators to make subjective decisions about the qualitative microwear features (Belmaker 2018). The research focus thus shifted to topographic data of dental occlusal surfaces textures on a microscopic scale (Belmaker 2018). In 3D optical microscopes, a light from a single source is split into two beams travelling across different paths, with sensors measuring the optical path difference between the two beams in order to identify the spatial interference pattern (Belmaker 2018). The most commonly used 3D microscope for anthropological research is the confocal microscopy (Belmaker 2018). This instrument uses either a white LED light or laser as its single light source – and more recently blue, red and green light – in conjunction with suppression of out-of-focus light to allow only the in-focus plane on the sample is captured by the photodiode through the aperture (Belmaker 2018).

Contemporary dental microwear analysis study ante-mortem micro-features on tooth enamel, indicating diet, and caused by the abrasion of exogenous particles and food items (Belmaker 2018). The post-canine teeth molded with polyvinylsiloxane dental impression materials and after following in vivo molding protocols, the molds complexity is used to indicate the amount of changes reflected on the surface’s relief at different scales (Percher et al. 2017). Since 2003, dental microwear studies have used surface metrology quantification methods that include SSFA (scale-sensitive fractal analysis) and ISO 25178 (“the International Organization for Standardization collection of standards relating to the analysis of 3D areal surface texture”) (Belmaker 2018). The dental topography is used to track the morphology of the occlusal form, while the 3D point cloud from CT or laser scanning and GIS software, reveal variables such as cusp relief, slope and angularity (Belmaker 2018).

It is assumed that the local diversity of the size and shape of different microwear features such as scratches and pits, increases with higher complexity (Percher et al. 2017). Carnivore teeth typically have thin enamel on their large canines, making them more prone to fracture under high bite forces but its evolution enables them to puncture prey through axial biting (Constantino et al. 2015). In contrast, herbivore chewing behaviour requires enamel that can resist degradation by wear, even though their chewing forces are relatively light, due to the frequency of tooth-on-tooth contacts (Constantino et al. 2015). Micromechanical models that quantify the role of particulate matter on tooth micro-and macro-wear are important in understanding how these patterns are reflective of diet.

The Relationship between Diet and Climate on Teeth

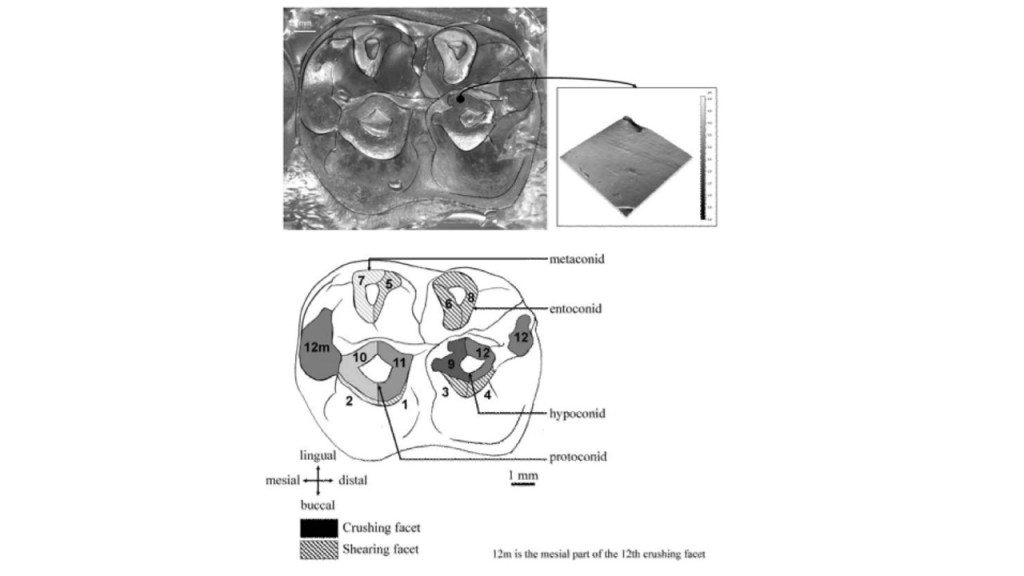

Apart from the physical properties of food, such as silica phytoliths in plants, that cause wear to enamel, a commonly mentioned source of wear that proves to be of greater impact, are exogenous particles that adhere to foods, such as grit and volcanic ash (Spradley et al. 2015). Silica phytoliths are present in herbivorous foods that are said to accelerate tooth wear and potentially lead to dental senescence (Spradley et al. 2015). For instance, herbivorous species typically encounter higher wear rates when they are known to be ingesting a high percentage of endogenous dietary silica (Spradley et al. 2015). A study of dental microwear textural patterns on a large free-range population of Mandrillus sphinx in Lekedi Park’s canopy forest, revealed their teeth wear as a good proxy for inferring assumptions about their diet (Percher et al. 2017). Figure 1 is a two-dimensional molar illustration of an individual male Mandrill, used to demonstrate potential areas of wear contact and support the use of 3-dimensional models as a more efficient tool to demonstrate microwear differences and impacts across and between species (Percher et al. 2017). Mandrills have been studied to have a highly diversified diet, largely composed of leaves, roots, mushrooms, small invertebrates and fruits, as well as a female hierarchy structure (Percher et al. 2017). The social ranking of females have been been hypothesized to affect an individual’s access to food resources according to their hierarchical status, therefore impacting the species’ feeding ecology (Percher et al. 2017). Using a combination of the dental microwear collection of 169 in vivo dental molds from 92 randomly trapped individuals from APril 2012 through December 15, and feeding ecology analyses, this study explored the effects of the season together with age, sex and social rank (Percher et al. 2017).

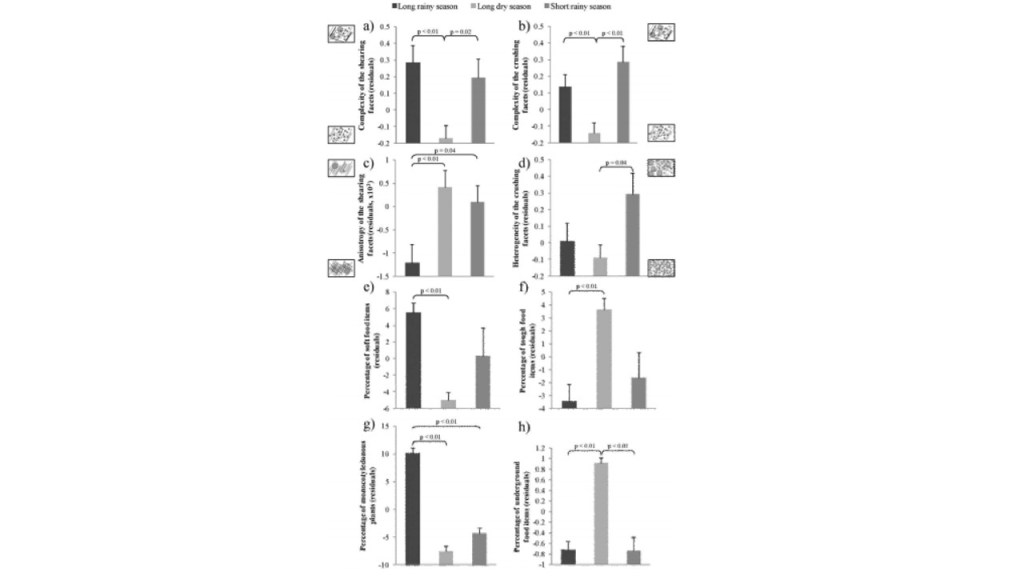

The study concluded that the feeding selectivity depended on the availability of resources, and that these resources depended on humidity, sunshine intensity, altitude or soil composition (Percher et al. 2017). Mandrills were observed to feed on significantly more soft food items compared to tough fibrous food items in the long rainy season, compared to the long dry reason – which is reflected in the complexity of shearing facets, which were noted to be more complex during the long rainy season compared to the long dry season where anisotropy is highest and complexity was at its lowest observed rates (Percher et al. 2017). Figure 1a illustrates the relationship between seasonality on the Mandrill’s diet using DMTA parameters (Percher et al. 2017). This observation may be due to the high presence of monocotyledonous plants being consumed by the mandrills during the long rainy seasons, compared to other seasons (Percher et al. 2017). During this season there are also variations in diet – with males feeding more on hard foods than soft foods compared to females, amd older individuals consuming harder food items compared to younger individuals (Percher et al. 2017). The rainy seasons are typically characterized as having a greater abundance of soft food items such as fruits, while also consuming small but hard fruit pits and seeds contained in the fruit being consumed, thus indenting the enamel and causing small pitting and increasing complexity (Percher et al. 2017). Among browsers, fruit eaters tend to have a higher complexity on their tooth surfaces than exclusively leaf consumers (Percher et al. 2017). The abrasive particles contained in these highly quartz-concentrated soils that cover the food items, with each single particle scratching the dental enamel, which may give reason to the increased anisotropy during this season (Percher et al. 2017).

Figure 1: Illustration of the dental wear facets of the second molar of an individual male mandrill (Percher et al. 2017). The purpose of this image is to illustrate the importance of using 3-dimensional technology to address features that are overlooked or ignored in 2-dimensional analyses – such as traces of adhering food remains between peaks, and the different functional aspects of the shearing facets (Percher et al. 2017).

Figure 1a: Graphic illustrations of the effects of seasons on the studied population of Mandrills’ diet. Small images of dental microwear are included to visually represent complexity (Percher et al. 2017).

The Relationship between Teeth and Grit

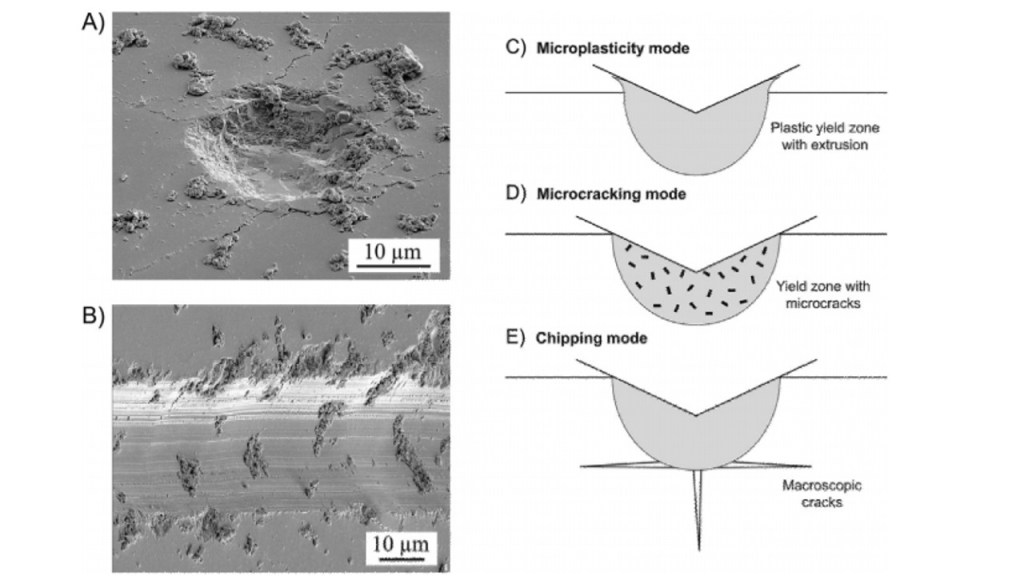

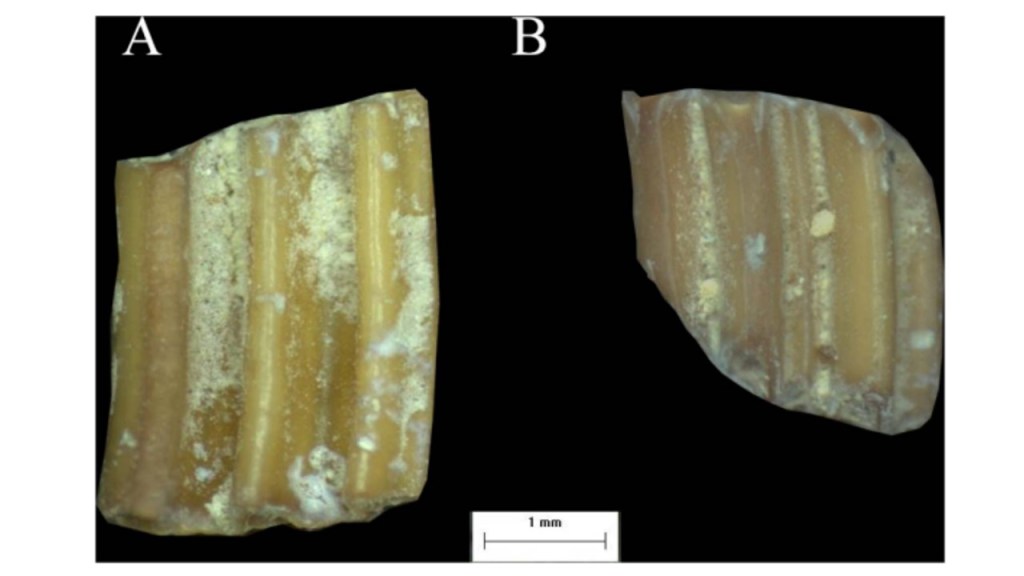

Contemporary studies on the mechanical properties of enamel and grit, have debunked earlier ideas of phytolith as being the culprit of microwear, by proving the quartz particles present in the material to having formed the basis of grit or dust, known now to be harder than enamel (Belmaker 2018). However, there are both in-vivo and in-vitro studies that have shown phytoliths as causing some microwear features and textures and that the formation of microwear is not avoided by material of lower hardness (Belmaker 2018). The most important aspect is then not the hardness of the material, but rather the “critical attack angle” – the angle in which a particle meets the wear surface that depends on the “toughness-to-strength ratio” of the wear surface and the geometrical property of the particle (Belmaker 2018). Figure 2 uses SEM imaging of microwear signals to illustrate the characteristic differences of wear on dental enamel (Constantino et al. 2015). As well, the effect of grit and dust particles, as well as phytolith properties on the formation of microwear, may differ depending on the species, due to differences in the mechanical properties and structure of enamel (Belmaker 2018). For instance, bovine enamel is typically 12.4% harder than murine enamel (Belmaker 2018).

Figure 2: SEM imaging of the enamel surfaces of extracted human molars, display microwear signals which are illustrated in images A and B on the left (Constantino et al. 2015). Image A represents axial contacts, whereas Image B represents sliding contacts (Constantino et al. 2015). The debris indentations are characteristic of brittle materials grazing along its surface (Constantino et al. 2015). The images on the right are cross-sectional representations of wear modes beneath sharp indenters, with image C displaying mild plastic extrusion at the edges of contact, D as observed to be severe or abrasive microcracks within the yield zone, and finally E as the ultra-severe case, with macroscopic chipping cracks experienced at the yield zone (Constantino et al. 2015).

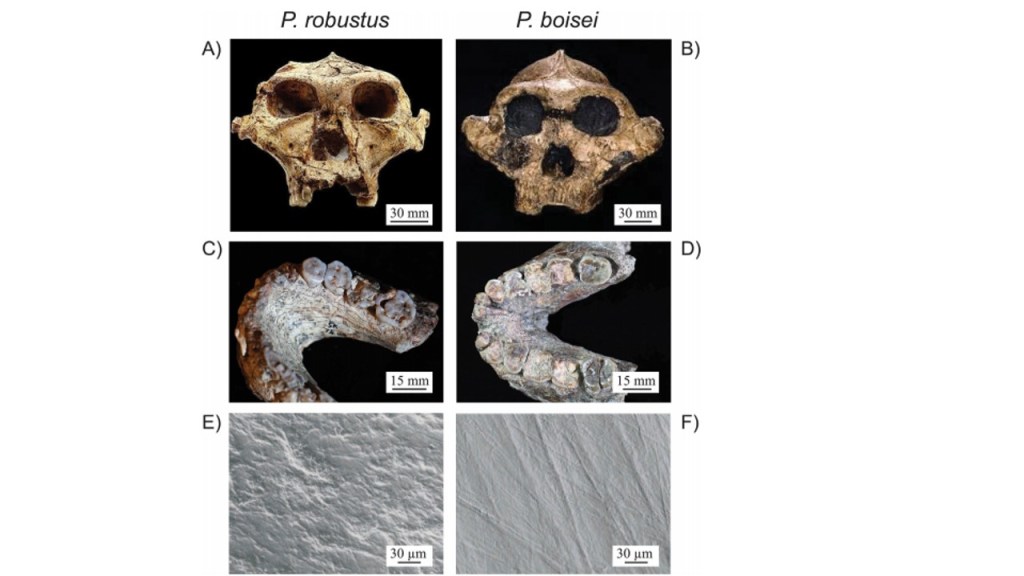

As well, despite the craniodental similarities of East African Paranthropus boisei and South African Paranthropus robustus, their dental microwear shows notable differences (Lucas et al. 2013). Both are assumed to consume a diet of primarily hard foot items, due to their shared features of large low-cusped thick enamelled post-canine teeth and large masticatory muscles (Lucas et al. 2013). Despite the heavy macroscopic wear, Paranthropus boisei shows evidence of finely scratched wear, suggesting a diet that consisted of tropical grasses and sedges – supported by isotopic evidence (Lucas et al. 2013). Australopithecus africanus dental morphology was also predicted to having adapted to eat hard foods, but microwear evidence collected from the scratches on dental enamel by phytoliths, quartz dust and enamel chips, shows that this species did not consume such foods regularly (Lucas et al. 2013).

The irony in this evidence is that though even the slightest amount of dust – regardless of whether the marks were true scratches or rubbing features – can cause greater enamel wear than many phytoliths, phytoliths may still dominate the microwear image, as seen in Paranthropus boisei (Lucas et al. 2013). Figure 3 illustrates the microwear data collected that illustrates the contrasting findings between macro and microwear (Constantino et al. 2018). The heavy wear from the early winter plumes has been suggested to be masked by the light rubbing from regular phytolith ingestion during the longer rainy season (Lucas et al. 2013). Protection from aridity is dependent on the microhabitat that the hominins occupied, with evidence from some modern groups in arid locations showing the possibility of heavy tooth wear (Lucas et al. 2013).

Figure 3: The naturally occurring dental wear and dentition of Paranthropus robustus and Paranthropus boisei (Constantino et al. 2015). Images A and B show the ectocranial crests of both species; images C and D show the tabular tooth wear in towards the dentin; and Images E and F data was collected through SEM imaging to reveal microwear damage (Constantino et al. 2015). This figure is used in this literature to show that despite the seemingly robust masticatory musculature of both species, microwear data analyses show dietary differences, therefore supporting the critique of solely using dental microwear and macrowear to make inferences on diet, as flawed (Constantino et al. 2015).

Critiques

Dental microwear analyses have been limited to studies of large mammals, overlooking the critical data that can be collected from small mammal samples (Belmaker 2018). The diet of small mammals for instance may change their diet inter-annually depending on the climate of the region (Belmaker 2018). For example, in temperate regions, Myodes glareolus primarily consume leaves and stems, but feed on harder items such as seeds and insects during the winter (Belmaker 2018). In warmer and drying regions and desert habitats, species like Microtus californicus has been observed to shift its diet from tough leaves and stems during the wet season, and hard grasses and seeds throughout the drier season (Belmaker 2018). That being said, dental microwear is not an accurate indicator of habitat; this is because there has been no correlation between the diets of secondary consumers and their habitat (Belmaker 2018).

As well, small mammals are susceptible to unique taphonomic processes that may not be experienced by most large mammals (Belmaker 2018). Initially after death, as a result of predation by raptors, digestive corrosion and breakage could occur, as well as the probability of trampling and weathering from exposure, as well as additional corrosion through acidic soil (Belmaker 2018). The effect of wear is illustrated in Figure 4. Several studies on the role of chemicals in the alteration of tooth enamel in large mammals have shown that the potential of an acid to erode the dental enamel is dependent on: “pH, titratable acidity, common ion concentrations” as well as the frequency and type of exposure (Belmaker 2018). Teeth have been found to be corroded by acidic soils of a pH between 6.1-6.6, and through roots and microorganisms, however basic soils with a pH of 9-14 “appear to have a diagenetic effect on bones and dentine, but not on enamel” (Belmaker 2018). The disjunction between what the species eats on a daily basis – evident as their microwear signal – and the rapid attrition caused by short events expressed through macrowear, complicates the relationship between dietary signals and the species’ actual diet (Spradley et al. 2015). Though grit, dust and phytoliths hardness data have been established, further research is required to fill the gap in data regarding the mechanical property of food items and abrasive food particles (Fiorenza et al. 2018). Standardized variables on tooth position, type, facet, and other variables, are required for each taxonomic group observed, in order to control for a multitude of factors and to ensure the accuracy of concluded hypotheses (Belmaker 2018). In terms of predicting the effects of climate change on complexity, the trophic level and size of the organism need to be considered (Belmaker 2018).

Figure 4: Image A and B are representative of two microtine molars from Ubeidya Israel. Both specimens show signs of wear (Belmaker 2018). However, specimen B shows moderate to high levels of digestion compared to specimen A who does not show clear signs of digestion (Belmaker 2018). This information is important because as it reveals, digestion can severely impact tooth morphology (Belmaker 2018). Ignoring digestion as a probable feature to investigate in microwear analysis, neglects a great deal of the global mammalian population – particularly small mammals that may experience this circumstance at higher frequencies (Belmaker 2018).

Conclusion

Dental microwear is a unique view into final days of the individual’s life, allowing researchers to hypothesize the habitats according to the narrow spatial scale (Belmaker 2018). The diet of the population has been observed to be known to change in accordance to the resource availability within their local environment, making diet perhaps the clearest indication of what vegetation was being dominantly consumed, as well as indirectly making inferences on climate (Belmaker 2018). As observed, there is a positive correlation between rainfall, vegetation cover, and species richness, as well as between resource diversity and temperature (Belmaker 2018). Small mammals have been underwhelmingly observed in current dental microwear data, even though they exhibit much greater diversity than large mammals – with over 50% of mammal species falling within this category, therefore showing a more diverse tooth morphology that is being overlooked in contemporary studies (Belmaker 2018). Researchers need to be wary of inferring causal explanations when formulating hypotheses on dental ecology on the basis of microwear alone, due to the dichotomy of divergent diets and distinct microwear processes have been observed to have indistinguishable macrowear outcomes (Constantino et al. 2015). For example, the absence of pitting characteristics on early hominin teeth should not be interpreted as the absence of tough foods in their diet; nor should the absence of scratches or microwear be interpreted as there being no leaves or structural plant parts present in their diet (Lucas et al. 2013).

References

Belmaker, M. (2018). Dental Microwear of small mammals as a high resolution paleohabitat proxy: opportunities and challenges. Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports. 18:824-838. Doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jasrep.2018.02.034

Constantino, P.J., Borrero-Lopez, O., Pajares, A., and Lawn, B.R. (2015). Bioessays. 38:89-99. DOI: 10.1002/bies.201500094.

Fiorenza, L., Benazzi, S., Oxilia, G., & Kullmer, O. (2018). Functional relationship between dental macrowear and diet in late pleistocene and recent modern human populations. International Journal of Osteoarchaeology, 28(2), 153-161. doi:10.1002/oa.2642

Lucas, P.W., Omar, R., Al-Fadhalah, K., Almusallam, A.S., Henry, A.G., Michael, S.,Thai, L.A., Watzke, J., Strait, D.S., and Atkins, A.G. (2013). Mechanisms and causes of wear in tooth enamel: implications for hominin diets. Journal of the Royal Society Interface. DOI: 10.1098/rsif.2012.0923

Percher, A.M., Merceron, G., Akoue, G.N., Galbany, J., Romero, A., and Charpentier, M.J. (2017). Dental microwear textural analysis as an analytical tool to depict individual traits and reconstruct the diet of a primate. American Journal of Physical Anthropology. DOI: 10.1002/ajpa.233337

Pineda-Munoz, S., Lazagabaster, I., Allroy, J., aEvans, A. (2017). Inferring diet from dental morphology in terrestrial mammals. Methods in Ecology and Evolution 2017, 8, 481–491 doi: 10.1111/2041-210X.12691

Spradley, J.P., Glander, K.E., Kay, R.F. (2015). Dust in the Wind: How climate variables and volcanic dust affect rates of tooth wear in Central American Howling Monkeys. American Journal of Physical Anthropology. DOI: 10.1002/ajpa.22877